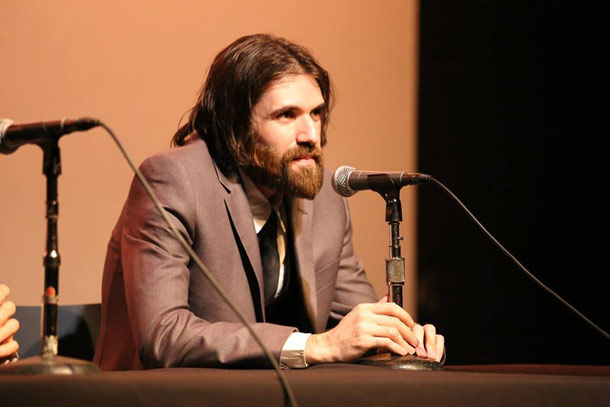

Arsalan Baraheni is an Iranian born, Canadian filmmaker, based in Toronto. His film, “Exilic Trilogy” recently had another premier in Gothenburg, in Sweden, at the International Exile Film Festival. The last Toronto screening of the film was in Harbourfrount centre, at Tirgan festival, the largest Iranian festival in the world. The trilogy consists of three films by Arsalan Baraheni, “light and sound”, “frame and wall” and alchemy and Dust. The films are poetic, visual and musical, featuring three of the most influential Iranian artists, a musician, a painter and a poet.

This review of the film was recently written in Sweden, by Andrei Trifoi in Gothenburg.

Exilic Trilogy: Creativity as resistance

Exilic Trilogy is a Canadian anthology film composed in three parts that depicts arts survival in exile. The director Arsalan Baraheni, an Iranian-born Canadian filmmaker, follows three Iranian artists as they reflect upon their creative expressions. Baraheni depicts their experience through a complex image composition where the poetic meets the social.

The first film in the trilogy is Light and Sound where we meet Soleyman Vaseghi, a musician that was forced to leave Iran in the aftermath of the 1979 revolution when his music was banned. In the second part, Frame & Wall, we follow the Iranian painter, Master Gholamhossein Nami, as he reflects upon his conceptual directions and the meaning of art. He also tells about his different art projects in Toronto that he has started as a way to connect the Iranian community. The last film, Alchemy & Dust, undeniably is the most personal, centred on Arsalan’s father, the writer and poet Reza Baraheni. In this film Arsalan tells us about his relationship with his father, how his childhood was affected by his father’s authorship and how the traditional fatherly son relationship evolved into a friendship where art established the emotional connection between them.

The cultural roots appear disconnected; a form that endows the artistic expression with a sense of melancholy. Exilic Trilogy is filmed in black-and-white and transverses in a slow pace that stresses the contemplative material. Exilic can be interpreted as a documentary film but the aim doesn’t seem to have been a search for a substance independent of the filmic process. In this regard it comes closer to the film essay whose structure tends to be characterised by the directors heightened presence.

If we approach Exilic from the perspective of its message we find that it reflects upon the question concerning the freedom of speech. But if we focus all our energy on this we risk missing the complexity of its narrative form. The film isn’t a political film, if by political we mean the presence of a clear political message in the film. Though it carries a political element in its form, its substance isn’t observable thematically; instead it progressively evolves throughout the narrative and overcomes the personal-social dichotomy. Art can never be independent in regard to the social conditions, it evolves through conflicts and the conflicts become a way of expressing what otherwise would remain unconscious. Creativity is omnipresent but the creative process is marked by a direction, a form born out of conflict. This condition is potentially productive in the way that it provides the artist with a means to express and a view of the expressed. In Frame & Wall, Gholamhossein says that arts true meaning can’t reside in its instrumentalisation, as a means for political ends. The work of art doesn’t require clear-cut means; the ideas, thoughts, opinions that the artist may have are reflected in the work of art – these more or less diffuse ideas become manifested in the work of art as the artists unconscious: “My political beliefs are hidden within the form”.

Creativity becomes foregrounded when the men talk about the reason for leaving Iran, their choice to live in exile as a creative necessity. The lack of creative outlets can be as good of a reason to flee as poverty or military conflict. In the end these social phenomenon have a common result in that they all reduce our perspective on the world.

In the last film we observe Reza Baraheni as he reflects upon the trials that forced him to flee Iran. The constant threats from oppressors and the fact that he was imprisoned twice is a testimony to the censorship that dictated/dictates artistic expression in Iran. Reza Baraheni tells us that he didn’t intend to become politically active but that the circumstances forced him to act. In Iran he is one of the founders of the writers association of Iran which wrote the text of 134, the name representing the 134 writers that were part of that text. It’s with in regards to this last film that we come across the director’s intention; he is trying to unveil – in a nonlinear manner – the survival of art in its exilic condition.

The separate films can very well be seen as self-contained but their composition suggests an aspiration that is larger than the parts seen separately. The scope is broader in that it exceeds the sum of its parts leaving a space for the viewer’s reflections. A profound utterance emerges in this last film when Arsalan tells us about something that his father used to say: “the artist is always in exile”. There is a parallel here between the creative act and mans condition in exile. Both these conditions are marked by instability, a search without clear grounds. However, if this existential separation is necessary, it shouldn’t necessarily be seen as static but as a means that enables the artist to impact his/her environment. The creative act can therefore neither be reduced to the social or the aesthetic; instead it signifies interchangeable forms in constant motion. A separation that allows the artists own voice to emerge in the act of creation but also transcend that act and thus point to the non-realized horizon of the becoming.

Written by Andrei Trifoi